Lead like a keystone species

-

Tom Parson

Tom Parson

At the recent Earthed Summit, Navajo scholar Lyla June Johnston presented a view of humankind that not only changed my view of our relationship with nature, but inspired a new approach to innovation.

Recently, I had the privilege of attending the Earthed Summit - which brings together visionaries, ecologists and change makers with a shared goal of moving beyond sustainability and into earth restoration.

The day was incredibly humbling - and I came away buzzing with inspiration. Not just for growing my own veg and what we can learn from fungi - but inspiration for my work, too.

One message really stood out to me, from Navajo scholar Dr Lyla June Johnston (pictured above), who challenged the widespread notion that humans are naturally destructive - at odds with nature.

"What if I told you that the earth needs humans?"

Lyla June Johnston

In recent times, we can't help but focus on the negative impact humankind has had on the planet. Whether through climate change, the mental health crisis, or the decline of biodiversity. But Lyla believes humans are actually crucial to the earth's natural survival.

Humans as a keystone species

Indigenous people have historically been referred to as "hunter gatherers," but Lyla points out that her people were more akin to farmers - caring for and cultivating the land around them.

She described the practice of cultural burning - turning dead plants into nutrient-dense topsoils, preventing trees from taking over grasslands, and protecting habitats essential for buffalo to thrive. "Many people think we followed the buffalo," Lyla explains. "But the buffalo followed our fire."

Lyla opened my mind to the role indigenous people have played as a keystone species in the evolution our planet.

Keystone species are species that play a critical role in maintaining the structure of an ecosystem and supporting biodiversity.

One of the most famous examples is the beaver, whose dams create wetland habitats essential to the survival of many other species.

I love this repositioning of humankind as an enabler of ecological thriving and wonder, rather than the current default perspective that humans are a blight on the planet.

Humankind is an enabler of ecological thriving.

This message was especially profound coming from Lyla, as someone so closely aligned with our planet. And the sentiment was echoed at the summit by Sâmia Biruany of the Huni Kuin people, who urged us technologically-enabled Westerners to not give up hope that we can support our planet to recover the damage it's endured.

Can we be a keystone in our work?

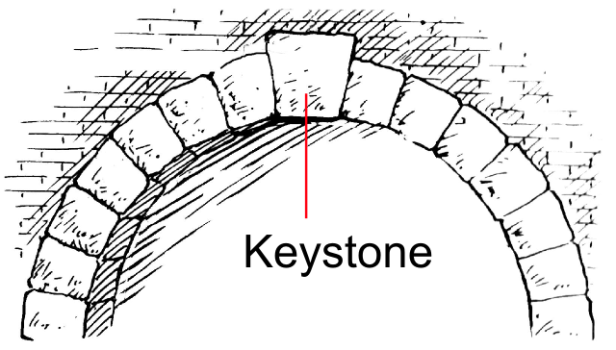

The term keystone species comes from the keystone in a bridge - the highest, most central stone that holds the least pressure, but nonetheless supports all other stones in the arch.

If humans can be a keystone species in nature, supporting life around us, what would it mean to act as keystones in our own ecosystems - our teams, organisations, and communities?

What damage are we trying to minimise? Environmental? Physical? Mental health?

What if we could do more than minimise harm - what if we could be the driving force behind positive, integrated growth and flourishing?

How can we move beyond sustainability, to active regeneration?

How can we move beyond a perspective of sustainability - simply sustaining and preventing harm...

Towards active improvement, regeneration and thriving for others - whether that's colleagues, customers or communities.

How do I get started?

How do we use Lyla's message to be better innovators within our organisations?

Indigenous people are well attuned to their environment - constantly listening to Mother Nature for guidance.

The same skill is required for effective innovation. Start by observing. Pay attention to the processes and people around you. Listen, perhaps using a 5-minute interview as a quick way to get started.

What problems can you see that need solving? Once you have a problem, try one of these techniques inspired by Lyla's talk.

Try a little selective burning

Select one process, task or meeting that no longer serves you or those around you. We are creatures of habit, and often don't realise when we're just going through the motions with no real benefit.

Just like the buffalo, new ideas will naturally gravitate towards the empty space this leaves.

Scatter a few seeds

Is there a checklist, template or data source your team relies on regularly? Is it accessible to those outside your bubble?

Publish your key assets to the wider organisation, or indeed for public consumption. Share your knowledge and perspective. Ask for others' resources, too.

Design for perpetuity

When making a difficult decision, think: "how will these options change things 5 years from now?" Factor this into your decision alongside other considerations.

As Lyla said, "What if our systems were designed to last forever?"

Beyond sustaining the status quo

Lyla reminds us we have a choice: to merely minimise harm, or to shape the conditions for life and value to thrive.

The same applies to the ecosystems we lead at work - teams, clients, communities.

The richer the soil, the greater the growth.